“I decided to become an artist when I was five, after I found a couple of my father’s pastel drawings, one of his dog and another of a parrot, stored away in a cabinet. I understood even then that some everyday objects of life were more important than others…From the time I was a boy and found those drawings by my father, I have always known that art transcends…”

After almost a half century, transcendent beauty is making a controversial “return” both in contemporary art and as a concept in contemporary art theory and criticism. In very different ways, beauty can be seen in the work of artists as diverse as Nicolas Poussin, Mark Rothko, Robert Mapplethorpe and Bill Beckley.

It is evident in full force in the latest works by Beckley. Perhaps the idea of beauty has always been at the center of Beckley’s aesthetics. While his photographic “story” montages of the 1970s and 80s communicated the irony that seemingly benign images may actually represent something sinister, and “truth” in text and image cannot be trusted, beauty in Beckley’s work was always present.

For nearly forty years, Beckley has challenged our understanding of art, ourselves, and the world Alongside experimental pioneers in the 1970s such as Sol LeWitt and Bruce Nauman, Beckley’s works at first shifted away from the pursuit of art’s more traditional goals: visual beauty, technical facility, and the expression of the artist’s “inner self.” Beckley used a wide range of media – photographs, installations, and performance – to assault artmaking traditions and the sterility of minimalism.

Drawn to the intellectual spareness of Brice Marden’s abstractions and the work of conceptualist Sol LeWitt, Beckley also was deeply inspired by the work of Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman. Beckley’s Roses Are, Violets Are, Sugar Are (1974) depicts the artist’s first use of flower stems, here seen against fields of red, yellow, and blue, inspired by Newman’s Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue series (1966–70).

Beckley’s flower stems appear as thin vertical lines or “zips” as Newman called them, against solid fields of primary color defining the spatial structure of the photographs, while simultaneously dividing and uniting the composition. Furthermore, Beckley’s photographs titled Stations from 2001 are named in recognition of Newman’s elegiac series of black and white paintings The Stations of the Cross (1958–66).

The late 1970s through the 1980s was a period of transition for Beckley

His work both questioned and embraced the intense theoretical dialogue of postmodernist works which combined installation, conceptual games, self-conscious texts and appropriated imagery from

the culture at large.

In the 1980s and 90s, Beckley’s conceptual photography became increasingly diverse as his imagery called attention to the way images carry meaning. Beckley’s narrative works integrated images and text to emphasize their multiple meanings and ambiguity as well as an awareness of their constructed nature, much like the work of artist colleagues Jeff Koons and Cindy Sherman.

But even these cerebral works had a finished balance and a formalist elegance. It is that balance and elegance that makes Beckley’s images from the last decade so compelling.

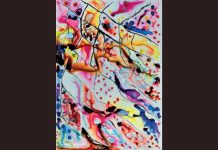

His photographs of poppies and calla lilies continue a rigorous attention to line, symmetry, and pattern, while they experiment with scale, serial repetition, and color. His lush Cibachrome close up images of glass vases and ashtrays investigate color and form as pure visual stimulation.

Photographed as fields of detail, the images belie their humble sources, and instead, encourage the viewer to reflect on the concept of beauty, the roles of beauty in culture and society, and its presence in contemporary art.

Rather than mere “pretty pictures,” Beckley’s large-format Cibachrome photographs of flowers and glass vessels are the culmination of four decades of making art about ideas. They are part of Beckley’s art history – steps along a trajectory from conceptual projects and text-object works to photographs of objects which resonate as culturally-loaded signs. And they are part of Western art history.

The linear verticality of Beckley’s stems and flowers set up a tension between object and void, and their repetition when hung in groups owes much to the influence of Frank Stella’s early Black Paintings with their methodical application of painted bands and stripes. Beckley’s flowers in the 2003 series Whirling Dervish blur as they spin in intoxicated slow motion evoking the same retinal shimmer as the visual reverberations of Stella’s stripes and voids.

Furthermore, Barnett Newman’s paintings of immense color fields cut vertically through with voided stripes of unprimed canvas or his “zips” are also referenced in Beckley’s works. Throughout this forty-year journey, Beckley’s art has explored the synthesis of opposites: truth and fiction, rational and intuitive, controlled and spontaneous, represented and real, permanent and ephemeral.

The latest photographs combine the purity of abstract visual experience with the primal exuberance of saturated color. For all their sultry beauty – whether fragile flowers or powerful swirls of bubbly glass – these artworks offer the viewer more than meets the eye.

It is up to the viewer to find those references and make those connections. Beckley’s exquisite, attenuated poppies, lifting their seedpods of opium, are beautiful images, but they are also images of decadence, captivatingly sweet, heady and dangerous. These are the opium poppies of Afghanistan which fund the Taliban and Al-Qaeda. And these are the heroin poppies that fuel the great jihad against the Western world and the United States.

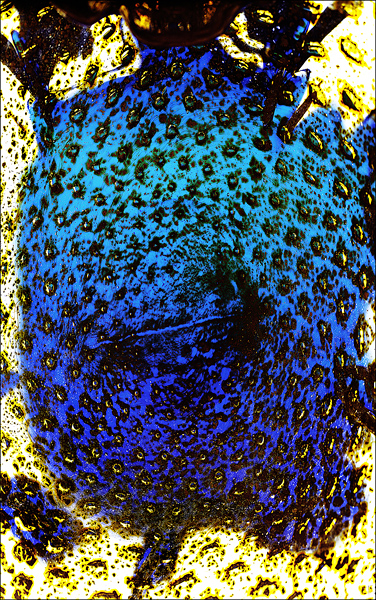

Beckley’s latest images – luminous, large-scale, photographs of glass objects like vases and ashtrays – take the viewer into a hallucinatory, swirlingmaelstromof saturated color, a state of romanticism, decadence and indulgence. The dangerous beauty of Beckley’s calla lilies and opium poppies has gone to seed, scattered into pools of sensual experience.

With their rich use of jewellike color, movement and ravishing patterns, these works communicate the substance and associative power of color. They capture our imagination with their visual complexity, as well as their enigmatic content, with titles such as “Baby Bear,” “Empty Spots,” and “The Adorable Blue Bottle Behind.” For both the viewer and artist, they are a new way of seeing.

Bill Beckley was born in 1946, and went to graduate school at the Tyler School of Art, Temple University, Philadelphia. Two professors were particularly influential to him – Stephen Greene and Italo Scanga. Color field painter Stephen Greene introduced him to Frank Stella and the dominant influence of minimalism in the late 1960s and 70s.

As a graduate student, his professor Italo Scanga (teacher of Bruce Nauman) was a great influence on Beckley’s thinking, and through Scanga, Beckley became friends with Bruce Nauman and Sol LeWitt.

Beckley has exhibited extensively in America and Europe since 1970. His works are in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum, and the Guggenheim Museum in New York; the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston; and the Sammlung Hoffmann Museum in Berlin. He teaches semiotics, literature, and film at the School of Visual Arts in New York and is the editor for the Aesthetics Today series, a series of books on contemporary issues in aesthetics, published by Allworth Press and The School of Visual Arts, New York City.