The years that Ralf Winkler (Penck) spent in Dresden from the Forties to the Sixties were the toughest. As a child in post-war Germany, he would play amidst the debris, and then, under the filo-soviet dictatorship, he would dodge the DDR’s controls, an oppressive reality particularly unbearable for those, like him, that could not bear any tyrannical imposition and limitation to expression.

In his early twenties, with other artists such as Baselitz, Poltke, Richter, Winkler left East Germany and moved to the West where the construction of the Wall had started. As a convinced communist, he chose to stay and deceive himself that he could change the actual circumstances.

Dresden was becoming East Germany’s technological hub, so he tried to adapt; he studied cybernetics but, even becoming a cultivated young man interested in experimentation, he never was a science man. Meanwhile, more and more talented scientists were migrating abroad. He immersed himself into music and became a jazz and rock expert and a musician playing drums and clarinet.

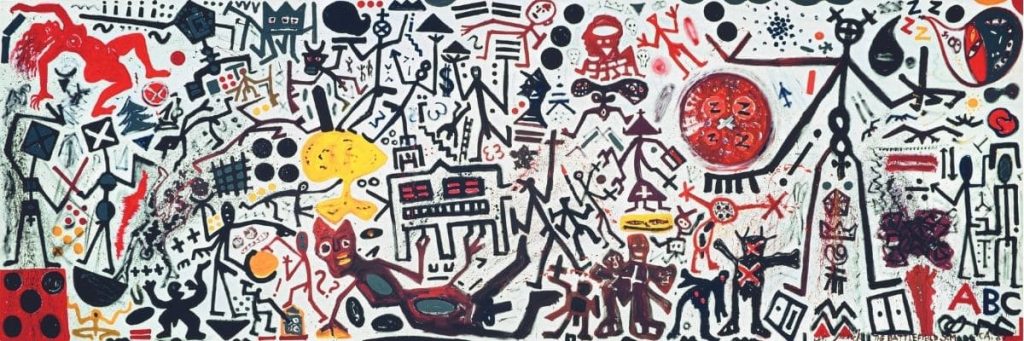

In 1961, he developed the first Welfbilder, a sort of graffiti in which he traced lean human figures with primitive weapons and worked out a personal network of symbols that anticipated the great work of Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring. Then he worked out the Standart theory on which he wrote: “In general, every visual phenomenon, once perceived in its totality, is a Standart”.

ON CANVAS, 340 X 1022 CM © 2021,

PROLITTERIS, ZURICH

A WORLD OF SIGNS

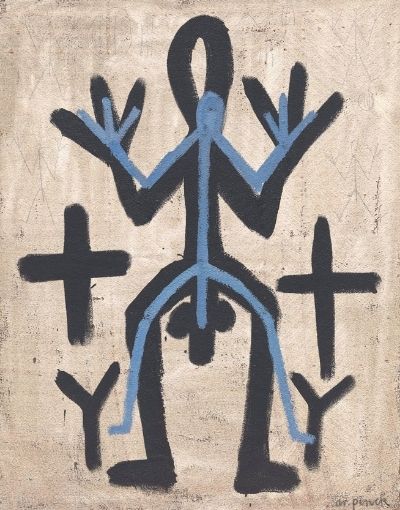

Since he did not want to align himself to the values of social realist painting, supported by the establishment and void of values, in 1968, he took the pseudonym of A.R. Penck and started to investigate the evolution of the sign to make abstract thinking visible.

The regime wanted the painters to represent “smiling individuals with bouquets,” while he had other dreams. Forced by the regime to go clandestine, he started exhibiting abroad with an alias. In the early Seventies, after approaching the western art scene (Duchamp, Warhol, Beuys) he declared that his Standard experience was over.

In 1980 there was a definite turn: he was expelled from the DDR and started a nomadic existence that led him to important galleries: from Koln (to Michael Werner) to Berlin, London, and Italy (Lucio Amelio and Enzo Cannaviello), and the US (to Ileana Sonnabend) and Switzerland.

COLOURS ON CANVAS, 127,5 X 98,5 CM

© 2021, PROLITTERIS, ZURICH

His language became chaotic, scattered relentlessly on huge canvasses, intensely visionary as if the West made him inebriated and at the same time tragically conscious of how illusionary everything was – in the bright lights he perceived the nightmare.

In 1981 at the Sonnabend Gallery in New York, he met Basquiat and Haring; in 1984, he represented West Germany Pavillion at the Venice Biennale with Lothar Baumgarten.

SCULPTURE AS INVESTIGATING THE SELF

In the late Eighties, he explored sculpture, which in the Sixties he had started with the Standard-Modelle: wooden, first, and then bronze, marble, felt along a pathway thought as a catharsis. In a picture of 1984, he is portrayed with an ax in his hand, suspended in mid-air in the act of hitting the matter.

The image reveals the impulse of physical and psychic energy compressed in his stout body, majestic, wild and tormented as a troll in Nordic mythology. His turn into sculpture was crucial, such as the retrospective “A. R. Penck” open in Medrisio (until 13 February 2022) shows.

Visitors at the Art Museum will see the three-meters bronze made in the Eighties Ich Selbstbewusstsein (I-Self-Consciousness), and one of his major plastic achievements, intended to question the role of the artist. The work opens the exhibition, curated by Simone Soldini, Ulf Jensen, Barbara Paltenga Malacrida, including forty paintings, twenty sculptures, and seventy drawings and books by Penck.

THE LEGACY OF A VISIONARY MAN

In 1988 he started his academic career when he was called by the Statal Academy of Dusseldorf and became a reference for young artists in Europe. As a summary of his subjective view of the spiritual history of humankind, he made the grandiose “panoramic” painting in 1989, The Battlefield, which recalls the Weltbilder pattern. More than three metres tall and ten metres long, it sums up, allegorically, the universal history of the world.

In the Nineties, Penck resumed his Standard-Modell, assemblages of cardboard, iron, rope, sticky paper, object trouvés, which he used to collect in the hope that a democratic art would come. He also developed felt sculptures: machines allowing him to navigate a world he constantly escaped, “without giving in to destructive attitudes of pathos, nor giving up the pleasure of signs and thoughts,” as Eric Darragon puts it in the catalogue of the exhibition.

In 2003, Penck was awarded the title of “Professor emeritus”. He died in 2017 when his latest retrospective at the Fondation Maeght in Saint-Paul de Vence was held.