Can we speak of female Muslim art? How much does gender identity influence artistic production, particularly in an Islamic context?

In Western culture, are there stereotypes which condition the understanding of art produced by women of Islam? These are a few of the questions I have tried to answer since beginning my studies in Persian Culture and career as an expert in contemporaryart.

It is important to take into consideration the reasoning behind artworks of female artists belonging to Islam, those whose artistic practice explores a contradictory world, characterized by the struggle against religious fundamentalism, whilst embodying pride to ones culture and origins.

Shirin Neshat and Ghada Amer, both conceive art as an instrument of social denunciation and of psychological introspection: with the use of imagery they conceive their interior world, their inner discomforts and difficulties and their desire to obtain a global identity which goes beyond sexual, religious and cultural differences. For Parastou Forouhar, Sukran Moral and Shadi Ghadirian, the use of a language which is at times ambiguous, allows to portray feminine contradictions in societies torn between modernity and tradition.

In the question of femininity, Neshat introduces elements of singing and music to expand the debate of the female body as mere object. Artists such as Shirin Fakhim, Firouzeh Khosrovani and Majida Khattari tackle the subject of prostitution, occasionally using an ironic tone and at others in direct confrontation with the type of masculinity, which implicitly consents to the treatment of women as commodity.

Shirin Neshat

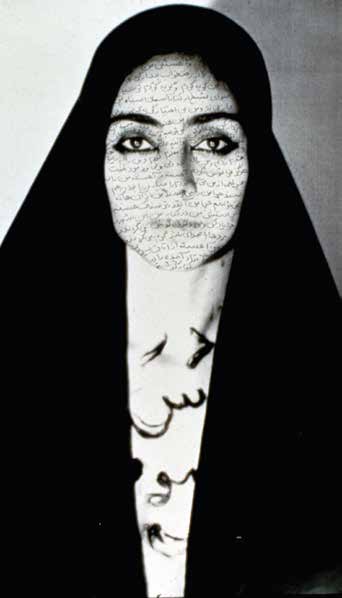

The work of Shirin Neshat strives to portray the complex social and religious forces that play an integral part to the identity and role of Muslim women in Islamic society whose subversive character originated at the beginning of her career in the works, Unveiled and The Woman of Allah.

These black and white photographic self-portraits, portray Islamic women in arms, veiled in heavy Chuddars. At first glance, they allude to the stereotype of a violent and masculine Middle Eastern regime while contrarily symbolizing women reclaiming power historically denied to them.

Ghada Amer

Ghada Amer explores the conflict of two separate identities:

one influenced by a Muslim upbringing and the other by western culture. Ghada strips both identities of their social codes with the use of ironic and desecrating language to highlight many contradictions and prejudices formed from the two different cultures: the extreme liberal model of the west and the typical model of Islamic Fundamentalism.

In Red Diagonales, (2000), the artist, inspired by action painting, creates imagery where the brushstrokes of acrylic paint partially hide and reveal the outlines of nude women embroidered on the canvas. This effect of negation becomes clear only after a moment of reflection. The technique of using bright colours in a blurring nature together with the cotton thread evokes a distinct history of painting, weaving a plot of signs and images that are interlaced like a refined arabesque.

Parastou Forouhar

Parastou Forouhar, of Iranian origin but resides in Germany, explores the psychological violence and political repression of totalitarian regimes. Farouhar combines a strong sense of attachment to her Islamic roots with the denunciation of the regime, one that in the name of Islam has forced a whole generation of women into silence.

In the photographic series Benham (2001), the ambiguity of the image plays a fundamental role. In the

distance the viewer immediately sees a series of marks, which upon further contemplation metamorphosize into a human figure, dressed in a Chuddar. As the viewer moves closer to the picture, it becomes apparent that the subject of the work is in fact not a woman but a man.

The man’s head is shaven, endowing his face with an undefined quality, at first glance, is more reminiscent of feminine traits. In this work, not only is the condition of women condemned, but also the social ‘consent’ which allows Islamic regimes to suppress the freedom of expression of women.

Sukran Moral

Sukran Moral of Turkish descent, who moved to Italy to flee the persecutions of 1989, documents the condition of women in reference to themes of marginalization, justice, religion and prostitution.

Her first appearance on the international art scene provoked a lot of attention: in 1994 she created Artista, a performance in which she played the part of Christ. By placing herself on the cross the artist claimed a kind of artistic androgyny, thus challenging the masculine world represented by the institutions of Islam and Catholicism with their equally misogynist view of society.

At the forefront of Moral’s ideology are the questions of female emancipation, and the juxtaposition of ideological conflicts and war.

Her criticism of misogyny is expressed in Speculum, (1997), in which the artist uses a gynaecological

examination table replacing the monitor with a vagina. History, alongside a history of art, have consistently objectified women, on one hand venerated for their chastity and on the other desired as an object of pleasure.

In Speculum, male pleasure is represented by a vision that penetrates a woman’s most intimate self, not only physically but spiritually; the woman is thus stripped of her identity and reduced to a squalid anatomical spectacle.

The works of these artists are not about a monotone voice on gender, race or religion. Rather than focusing on the Hijaab, what about trying to understand the message embedded in the art of these artists that can easily interconnect with our own lives creating a fresh flux of creativity and experience.

I remember that during my first visit to Iran, one of my main expectations concerning the work of the female students at the Iranian Academy for Arts, and of the female Iranian artists that I met, was connected precisely to the ‘question of the condition of Islamic women’, which I believed would be

often and assiduously present in their artistic work.

The reality that I discovered, however, was to the contrary. The work of most female artists of Islamic

religion is not dedicated to an art of ‘gender’, if we can define it thus. A certain amount of ‘intolerance’ towards the expectation of the work of female Iranian artists should solely reflect the question concerning the position of Islamic women’. Tired of being depicted in western eyes with the cliché of the subdued and subordinate woman, they strive to shake off this image that has been applied to them and to be free from the western expectations connected to female Islamic art in general.

The artistic production of these female artists goes beyond the vision of the female Muslim artist who speaks exclusively of veiled women, imbued with ethnocentric clichés. These wonderful artists take part in a global discussion that is useful for each one of us, they help us reflect upon our own individual struggles: where are we, at what point did we stop and which direction do we have to take in order to

go forward? It is a journey that has to be personal contribution.