Your approach to painting by way of “action, reflection and reaction” is said to unfold sometimes over years in order to develop a piece to its full expression.

Can you give us a glimpse into that process from the moment when you are face-to-face with a blank canvas?

Painting a new picture is nearly always a difficult undertaking since it involves going to one’s limits and still getting surprised, even after 30 years of painting. Disappointments and frustrations are inevitable because the path to a new image, which is always unique, can be excruciating.

Action, reaction and reflection are inseparable. I try to create a form out of every situation and every part of life I encounter. I then concentrate these and attempt to visualize them through painting. When I stand in front of a blank canvas to begin painting, I often do so with Fabian strategy1, very similar to avoidance. Common first steps: brushing the atelier floor, stirring the paint, grounding the canvas and going for a coffee. There is an abundance of manual, ritual work in the atelier; the step to direct artistic

work has a lot of transitions.

After I choose the format, I use my own pictures, small newspaper clippings, or small-scale structures which I transfer onto the canvas through painstaking work, to transfer myself into the picture. In the best case I reach a state in which my conscious and unconscious minds nearly unite and carry me determining my actions.

Painting requires certain conditions: inner peace as well as the ability to become immersed in it. You take a step out and then get back in. I try to create a rhythm that has different frequencies. It is not an unchanging beat. One must learn to operate at different speeds.

Sometimes painting is like dancing on a hot stove: everything has to be fast, otherwise you get burned. This includes mishaps-accidents that will inevitably occur-but the crises promote the growth and ripening of the images.

They lead you to do things that you have never seen before in order to keep or destroy something in the picture. In retrospect, I’m usually happy about having dared to leave my usual path, having allowed for the risk of the unknown.

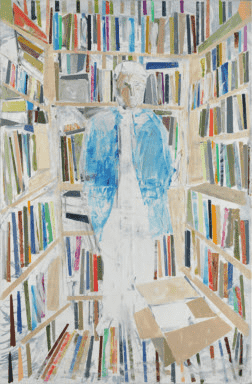

Where do you draw your inspiration for the imagery that populates your work-your trails and movements of tiny people, the stacks upon stacks of books, the ridges, trees, close-ups and bird’s-eye views of the topography which is beyond natural landscape?

Images are shaped out of existing images. I have no theories; the emergence of my thoughts does not follow a particular strategy. Although today my approach to painting, and thus the images produced, is very unlike the one I had 20 years ago, for me it is a continuous line, it is my own way. The image does not interest me that much, my passion is painting. There are recurring themes; some subjects come to me and are used as a means of transport.

The starting point is often a mixture of stories, previously seen pictures of any kind, and preferences for specific locations and shapes. The motives are related to my experiences and my own biography; I like the familiar. It is the material I come back to, when I have found the necessary distance.

Each painter handles his experiences and perceptions in his own characteristic manner. I can approach things best either by proximity or a type of bird’seye view from a great distance. This is a form of development which does not seek to map reality but rather to give form to an internal process.

Your work is seen as more closely associated with the German Romantics than the Expressionists and has been compared to the seminal work of Caspar David Friedrich. Your allegorical concepts, understated hues and tiny figures dotting expansive landscapes all reveal a contemplative approach. Where do you find your work more closely aligned within the different art movements?

I have no role models. The first catalogues that I bought were from Bacon, Giacometti and Soutine, all of whom are artists that I was inspired and challenged by as a young painter. I see myself as a romantic, but this is more of an attitude than a style. I think there is very good art in every category, but wouldn’t categorize myself in any. I am primarily focused on questions of meaning, not aesthetics.

You have witnessed and participated in over three decades of art history in the making. From what you experienced, do you think that artists influence the spirit of the age or vice versa?

Art is always a reflection of our time. It acts as an early warning system. The constant confrontation with the media and global structures changes our communication, our viewing habits and our perception. We are confronted with an unmanageable flood of images every day. There is no justifiable ranking among the different modes of representation.

To me it’s always about the whole thing. For me making art is about having a special view of the world and the objects in it. Because the real concerns are timeless, the questions must be asked over and over. Maybe they will never be definitively answered, but they must be set “right” for each and every time frame.

Which contemporary artists do you see as representing the zeitgeist, both influenced by, and influencing, our world today?

There are always “beacons” which seem to be a necessity. I respect and value many; sometimes I even feel envy. But in order to answer this question, I would have to say something that I truly do not feel. I do not think an artist can honestly answer this question. For me, it is always the sum of everything.

Do you prefer to play an active role in creating the exhibition space when showing your work?

In a planned exhibition one should always take the place into account; the architecture of the space has to be considered. This includes the proper spot to hang each picture. In front of each image there is an imaginary semicircle which is the space that a picture claims. Certain images get along with one another, complementing each other; others are total loners. The complexity of the painting is just as relevant as the distance between the viewer and the image itself. The observer’s mission is to find the right distance to the image.